Introduction#

Slavery was widespread in antebellum Northern Virginia. In Arlington and Alexandria, which were then both part of Alexandria, there were 1,386 enslaved people documented by the 1860 census.1 Alexandria was home to one of the largest slave-trading operations in the country.2

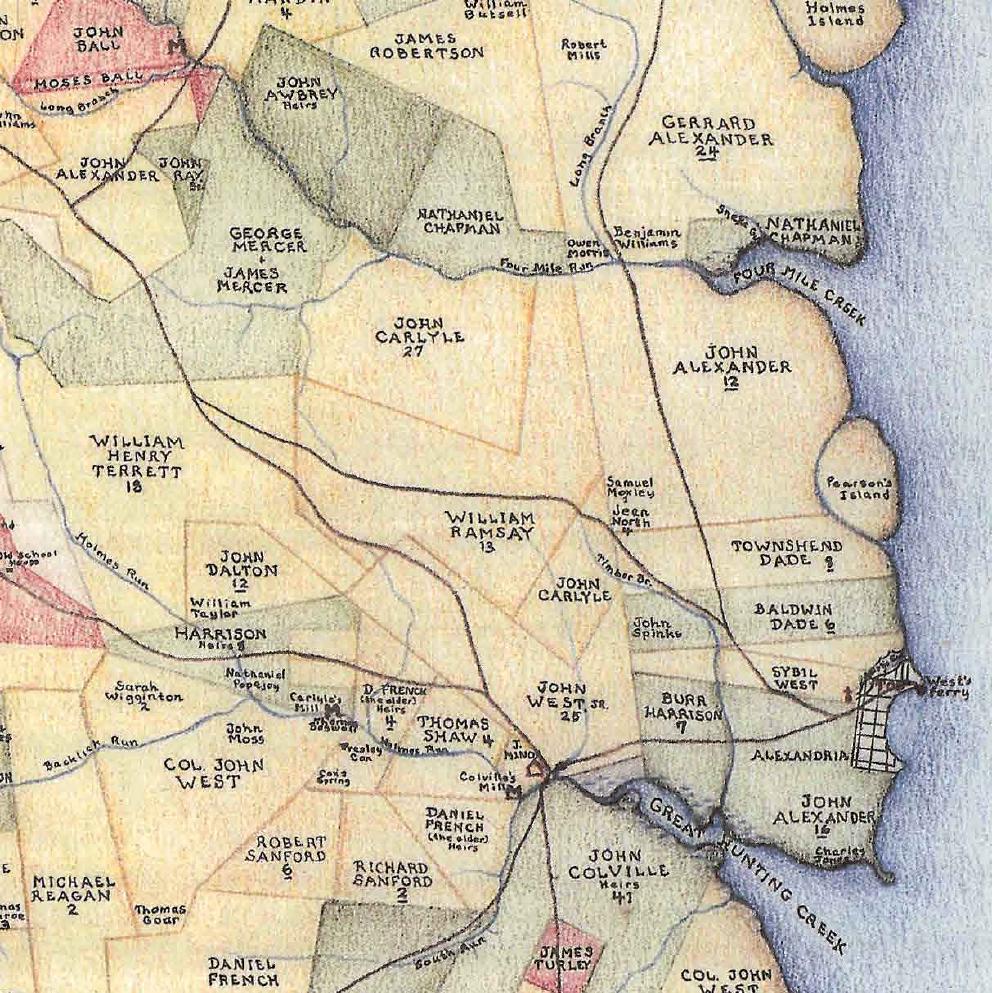

The area we now know as Fairlington was no exception. This widely-used interpretative historical map by Beth Mitchell3 shows that John Carlyle owned this land, and that based on court records there were estimated to be 27 enslaved persons working there. The farm there was called Torthorwald, but would later be renamed Morven.4 The residence at Morven was located at what is now South 31st and Columbus Streets, approximately where the building for 4820-4850 31st Street South presently stands, and/or on the area in front of it.5 A cropped section of the map is below, with Torthorwald/Morven in the center, bounded by Four Mile Run to its north.

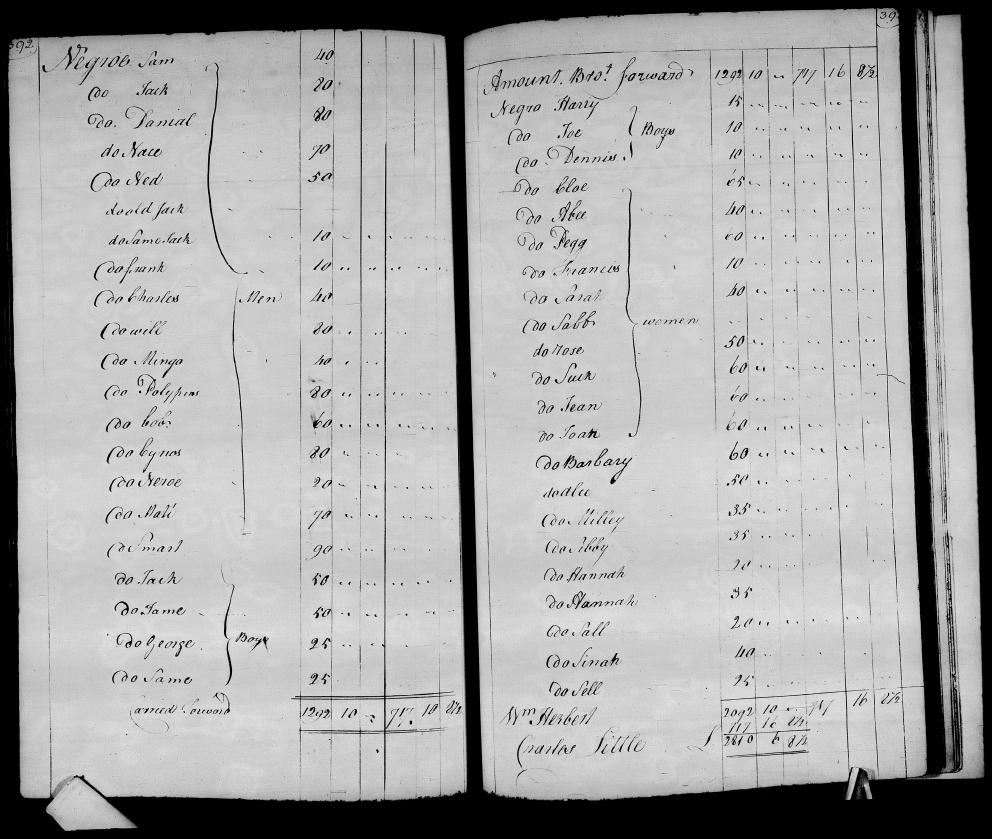

1780 Inventory#

A detailed inventory of Carlyle’s assets at the time of his death in 1780 also provide a glimpse into slavery at the estate.6 43 enslaved persons were listed among assets like books and furniture to be passed along to heirs.7 Their names were:

- Sam

- Jack

- Daniel

- Nace

- Ned

- Jack

- Jack

- Frank

- Charles

- Will

- Mingo

- Polypus

- Bob

- Cyrus

- Neroe

- Matt

- Smart

- Jack

- Jack

- George

- George

- Harry

- Joe

- Dennis

- Cloe

- Alce

- Pegg

- Francis

- Sarah

- Sabb

- Rose

- Suck

- Jean

- Joan

- Barbary

- Alce

- Milley

- Sibby

- Hannah

- Hannah

- Sall

- Sinah

- Sell

Newspaper ads#

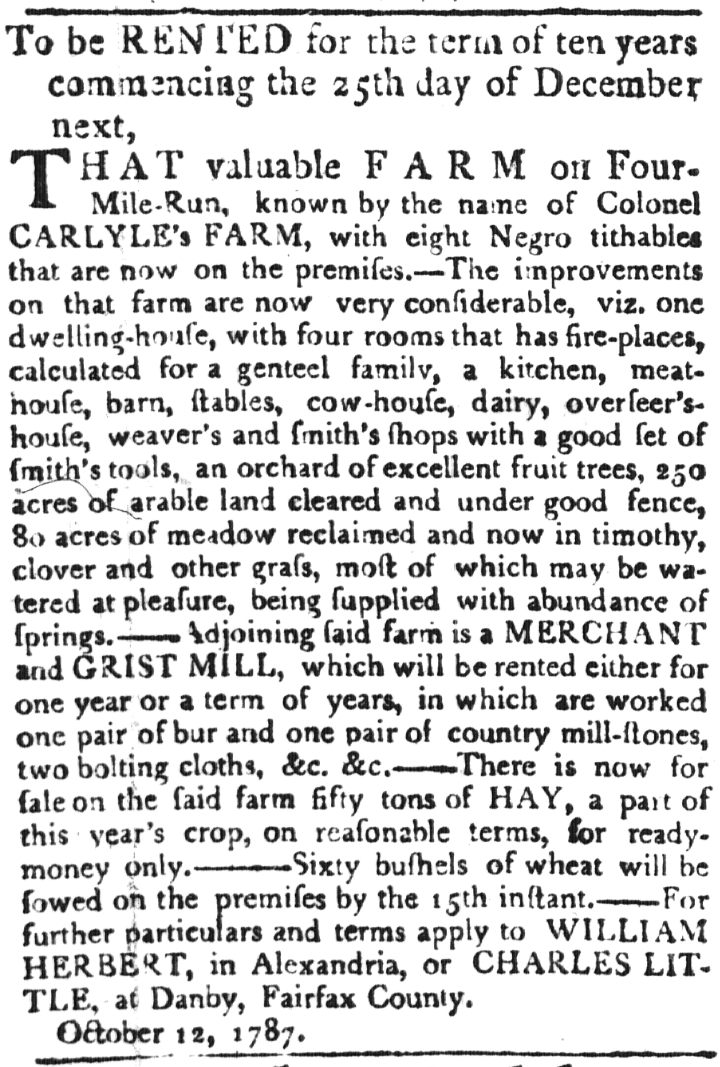

After John Carlyle’s death, the farm was passed to his grandson, Carlyle Fairfax Whiting. There is ample evidence that slavery continued during his tenure. For example, Whiting published an advertisement in the Alexandria Gazette in 1787 that listed the farm’s assets, including “eight Negro tithables.” These were enslaved adults; there likely would have been additional enslaved children.

From the October 18, 1787 edition of the Alexandria Gazette.

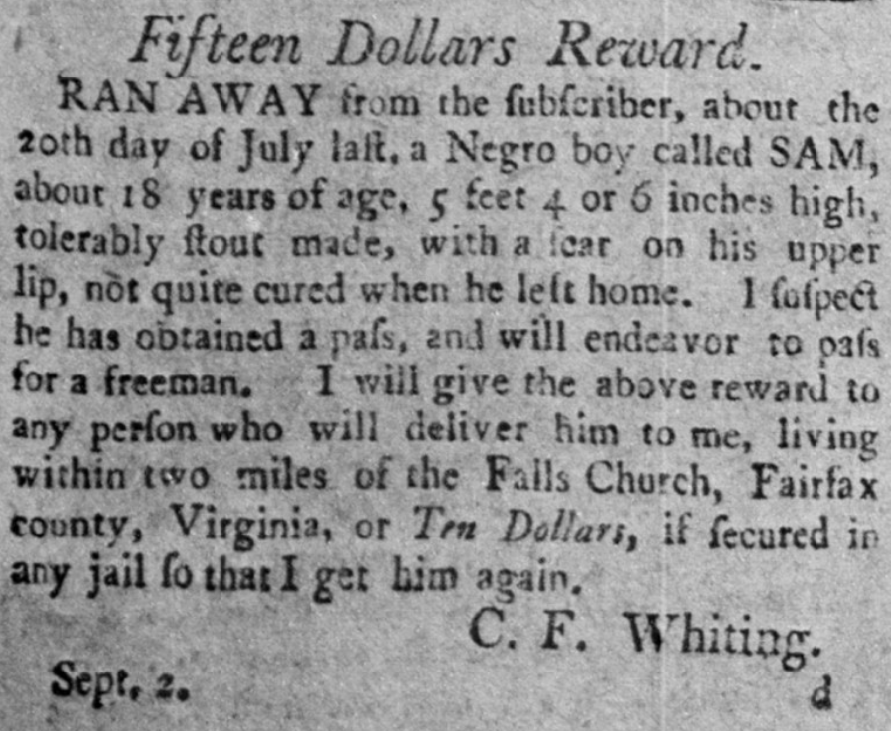

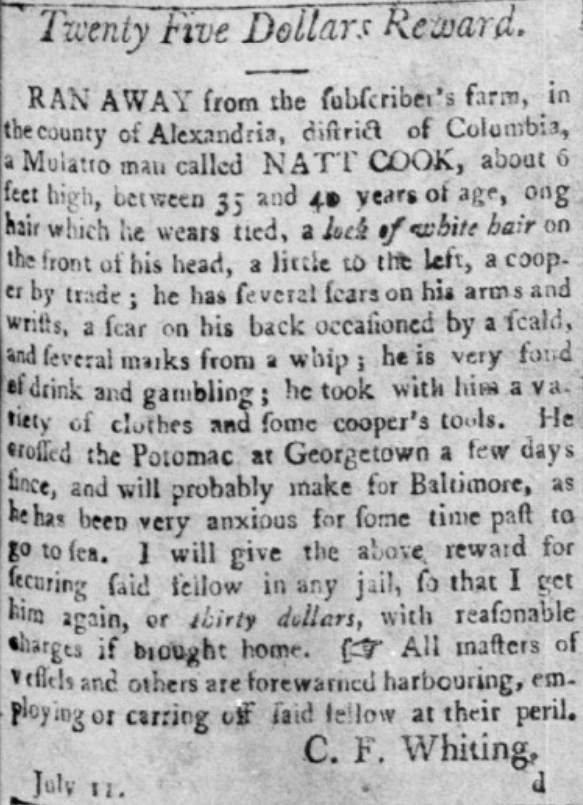

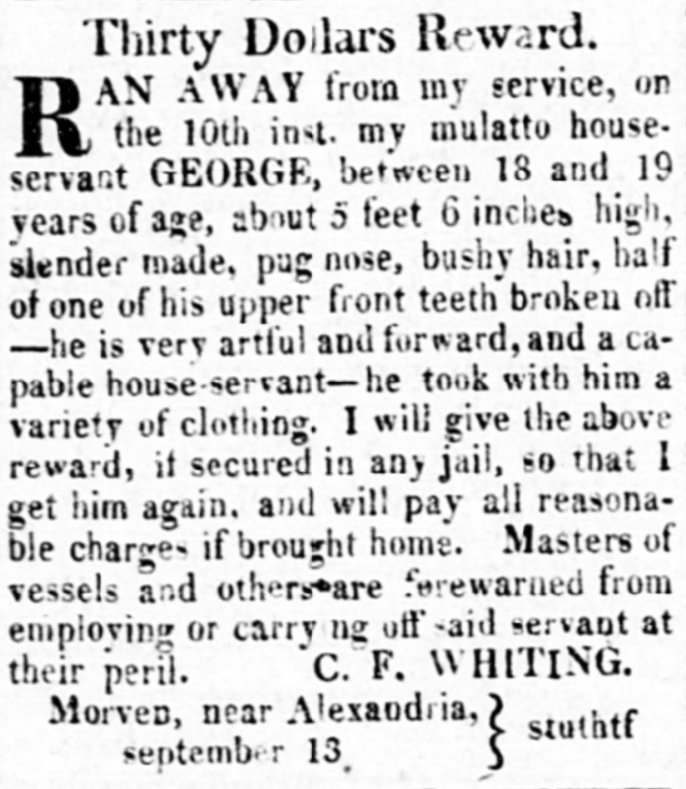

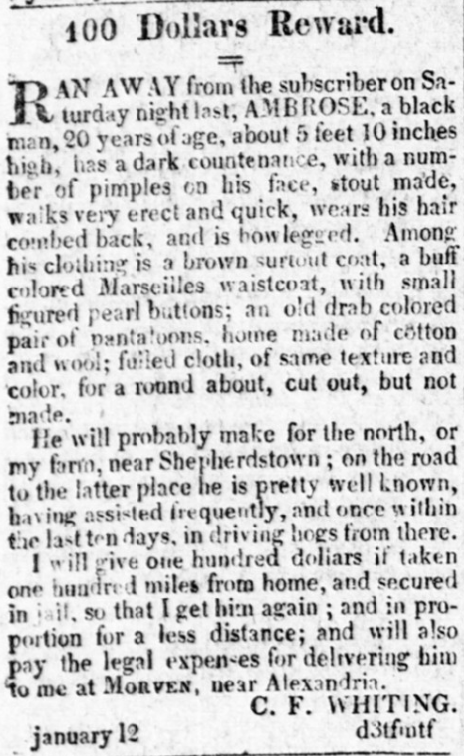

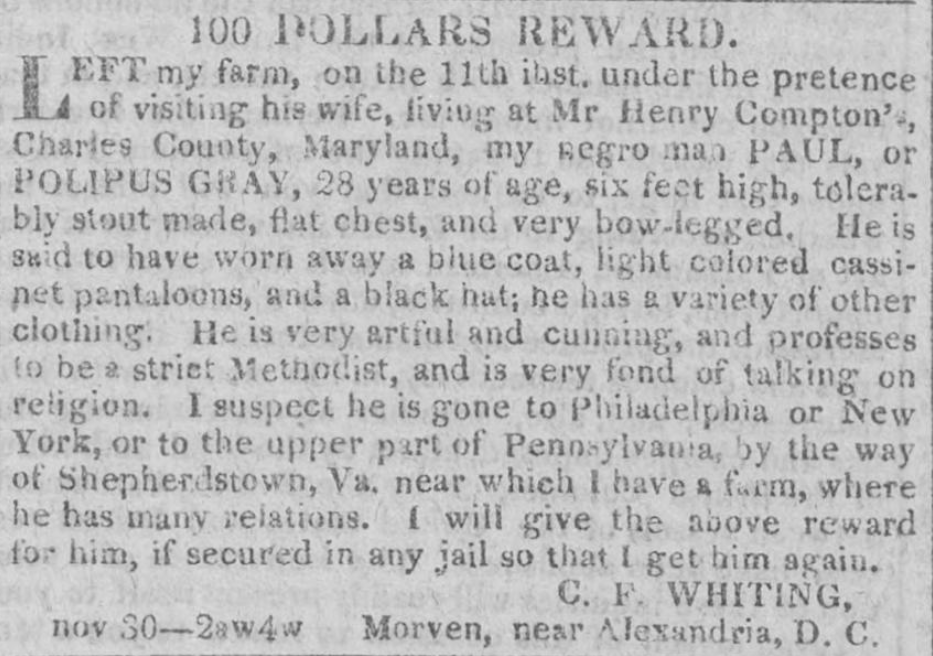

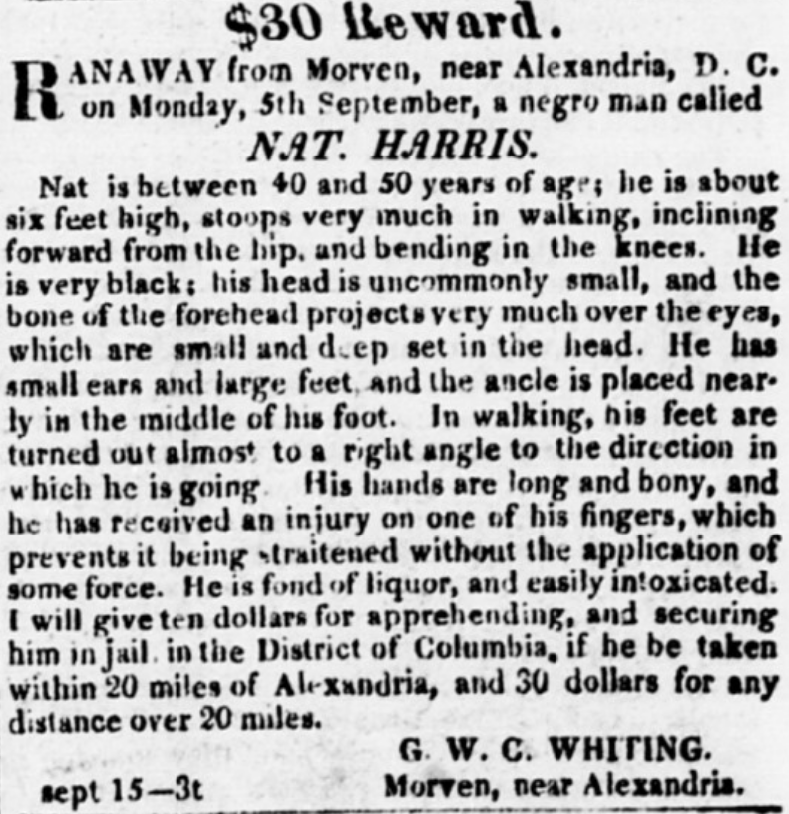

In the years that followed, Whiting published several ads in the Alexandria Gazette seeking the return of enslaved persons.

From the September 23, 1803 edition of the Alexandria Gazette. From the August 30, 1804 edition of the Alexandria Gazette. From the September 20, 1817 edition of the Alexandria Gazette. From the January 14, 1819 edition of the Alexandria Gazette. From the December 13, 1826 edition of the Daily National Intelligencer. From the September 26, 1831 edition of the Phenix Gazette.

Some of these ads ran in multiple successive editions, indicating that efforts to recapture the individuals were not, at least initially, successful. The ad originally published in September 1817 was republished regularly until April 1818. Additionally, note in the 1804 ad the writer’s detailed familiarity of scars remaining from physical assaults, including a scald and a whip, that the enslaver or the overseer may have imposed at Morven.

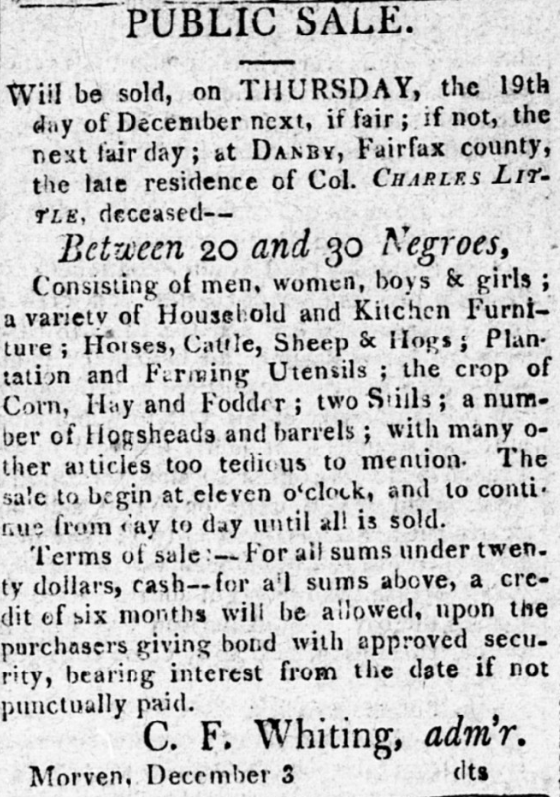

At least once, Whiting advertised a sale of individuals he had enslaved. This 1811 sale, to take place in Fairfax County, included “men, women, boys & girls,” as well as furniture and livestock.

From the December 9, 1811 edition of the Alexandria Gazette.

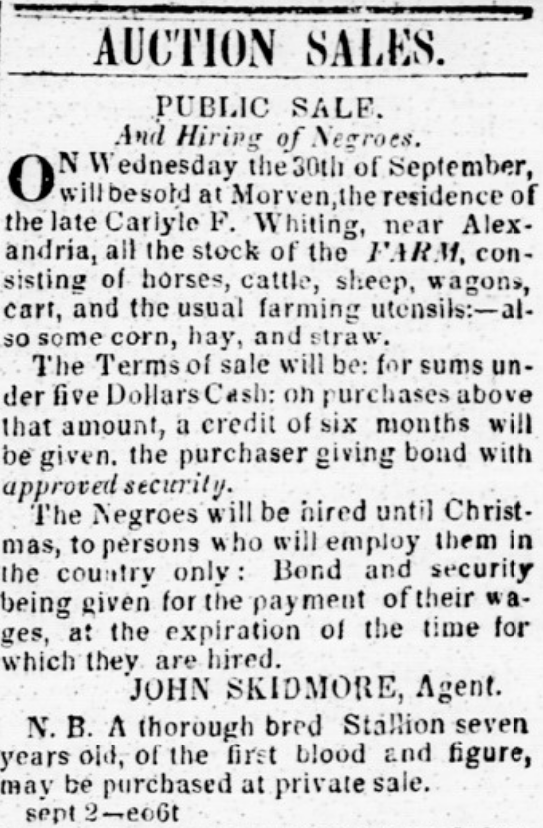

Charles Whiting inherited Morven upon his father’s death in the early 1830s. In September 1837, the younger Whiting advertised that he would be hiring out persons enslaved by him until Christmas.

From the September 2, 1837 edition of the Alexandria Gazette.

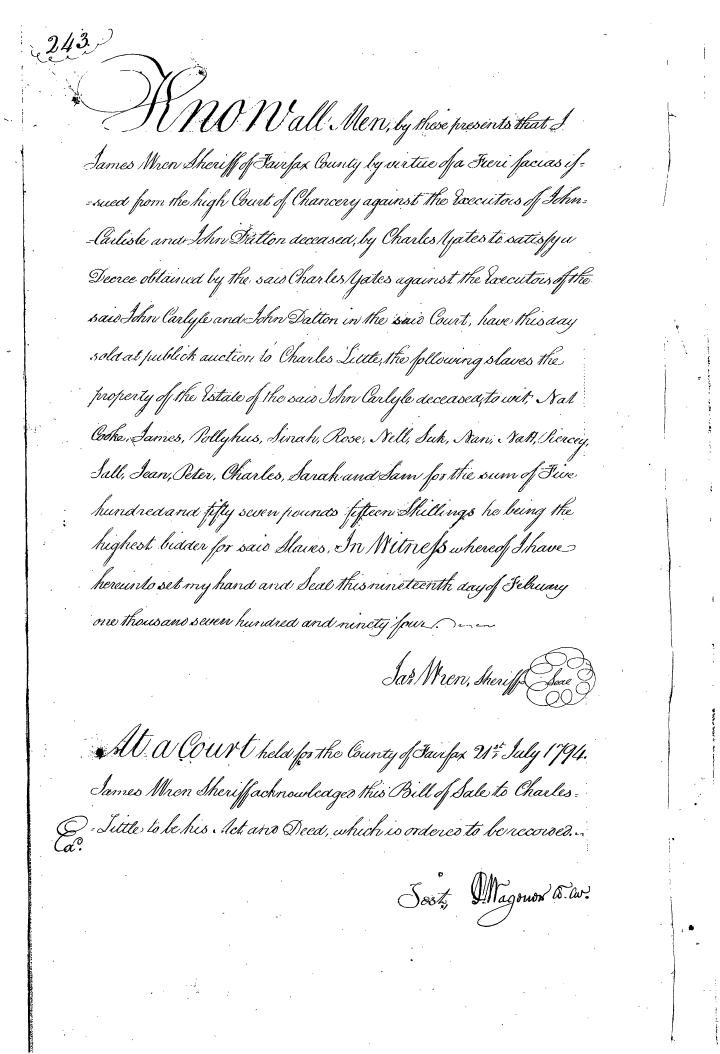

1794 Auction#

Following John Carlyle’s death, some enslaved persons were auctioned off rather than inherited outright in order to satisfy debts against the estate. We identified a list of these individuals, and have listed the names below.8

- Nat Cooke

- James

- Pollyhus

- Sinah

- Rose

- Nell

- Suk

- Nan

- Natt

- Piercey

- Sall

- Jean

- Peter

- Charles

- Sarah

- Sam

It is not known how many of these individuals were enslaved at Tortherwald/Morven rather than Carlyle’s other properties. Some of these individuals were likely the same as those who were listed on the 1780 inventory.

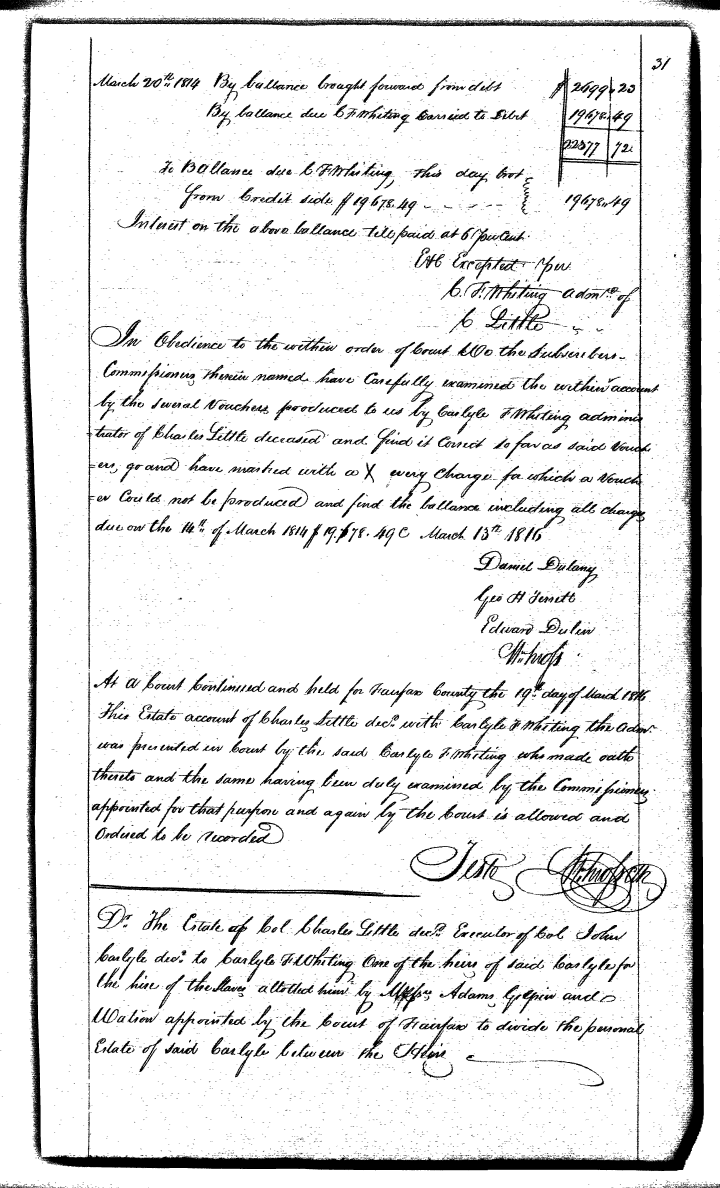

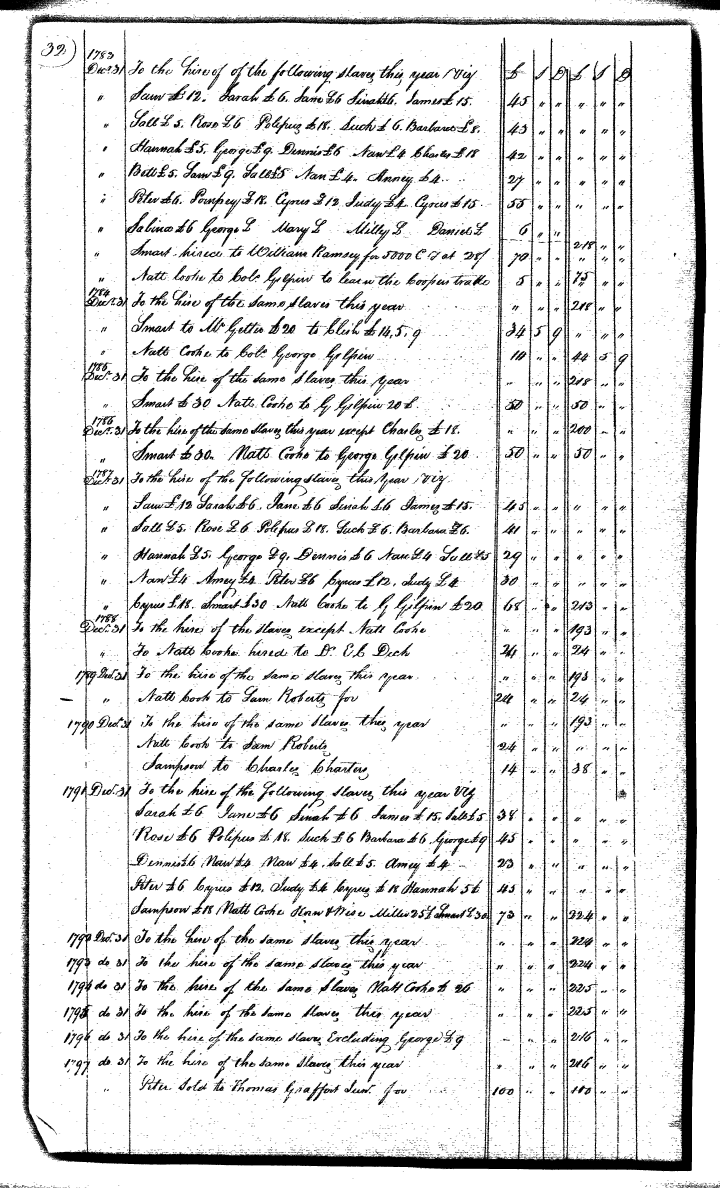

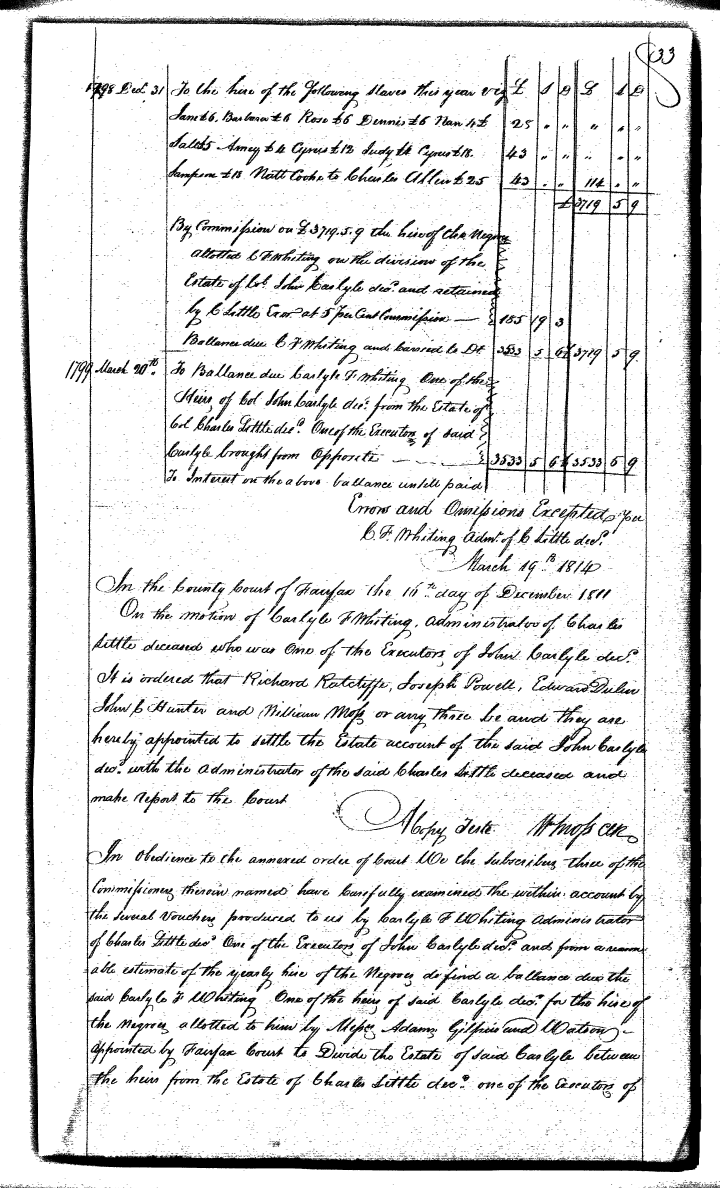

1816 Will#

An 1816 will from an executor of John Carlyle’s estate tallies the revenue generated from renting individuals who had been enslaved by Carlyle. The revenue was then paid to Carlyle’s grandson and one of his heirs, Carlyle Fairfax Whiting. This document demonstrates how frequently enslaved people were moved between different plantations and estates, and how difficult it must have been to maintain a semblence of a family unit among them. It also makes perfectly clear that enslavers benefitted financially from their labor.

Note that “Natt Cooke” is listed on this document as being rented out in 1783 “to learn the Coopers trade.” We imagine that this is the same “Natt Cook” who was advertised as having escaped in 1804 “with some cooper’s tools.”

The will documents, and a list of the enslaved on those documents, are below.9

- Natt Cook

- Sam

- Sarah

- Jane*

- Dinah*

- James*

- Sall

- Rose

- Polepus

- Suck

- Barbara

- Hannah

- George

- Dennis

- Nan*

- Charles

- Sall

- Pompey*

- Cyrus

- Judy*

- Amey*

- Smart

- Sampson*

- Polipus

- Peter*

* - Name is unique to this record

Conclusion#

Most enslaved individuals in Alexandria (which included the area we now know as Arlington) gained some freedom through the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862.10 The Emancipation Proclamation definitively freed the enslaved in Alexandria in 1863.10

Morven, as photographed in the 1930s. It was razed when Fairlington was constructed.

-

1860 census data. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1860/population/1860a-36.pdf#page=17 ↩︎

-

“History of Alexandria’s African American Community.” https://www.alexandriava.gov/historic-alexandria/history-of-alexandrias-african-american-community ↩︎

-

An interpretive historical map of Fairfax County Virginia in 1760 showing landowners, tenants, slave owners, churches, roads, ordinaries, ferries, mills, and tobacco inspection warehouses. https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=cca6b4a3ef644dbfa89e16b6feb515fe ↩︎

-

Alexandria Times, April 17, 2008. https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/attic/2008/attic20080417torthorwald.pdf ↩︎

-

This is based on three maps spanning the time period that Morven was known to have been standing that all show a rectangular building at this location: a Civil War era-map, a 1900 property map, and a 1936 property map. Additionally, this was the location of a water tower in Fairlington’s rental era (1940s-1970s) according to archived USGS maps, and Fairlington at 50 cites the water tower as having been the former location of Morven. ↩︎

-

“Fairfax, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89PC-2G77?view=explore : Oct 24, 2025), image 225 of 252; Image Group Number: 007644611 ↩︎

-

Our gratitude to Memorializing the Enslaved in Arlington for identifying these individuals and the source record. https://enslavedarl.org/s/memorializing-the-enslaved-in-arlington/item/35456 ↩︎

-

This record was obtained from the Fairfax County Circuit Court Historic Records Center. Fairfax Deed Book X-1, page 243. ↩︎

-

This record was obtained from the Fairfax County Circuit Court Historic Records Center. Fairfax Will Book L-1, pages 31-33. ↩︎

-

“Community: The Race to Freedom.” https://www.alexandriava.gov/cultural-history/community-the-race-to-freedom ↩︎ ↩︎